KRISH MACKERDHUJ - A STRUGGLE HERO WHO STOOD UP

AGAINST RACISM IN SPORT AND SOCIETY IN GENERAL IN SOUTH AFRICA

BY SUBRY GOVENDER

INTRO: At a time when South

Africans are enjoying the full benefits of international sport, it’s

appropriate to recall the struggles of our sporting administrators who made

this possible. Veteran journalist - Subry Govender – contends in our ongoing

series on Struggle Heroes and Heroines that the role played by non-racial

sports administrators was a vital element in the broader struggles for the

creation of a non-racial and democratic South Africa. One of the leaders was

Krish Mackerdhuj, the former president of the non-racial South African Cricket

Board, who passed on, on May 26 2004.

It was a period in the 1980s

when white cricket at that time was feeling the full impact of the isolation of

South African sport that Krish Mackerdhuj, who was president of the non-racial

South African Cricket Board(SACB), came to the fore. He and his fellow

anti-apartheid sports administrators were taken aback by moves by a former

captain of the whites-only national cricket team, Ali Bacher, to lure the

former West Indian cricket great, Clive Lloyd, to visit South Africa to

intervene between white and non-racial cricket administrators. Bacher was the

CEO of white cricket at this time and he was busy preparing rebel tours to

break the international isolation of white cricket. This isolation was led by

all the former colonised countries such as India, West Indies, Pakistan and Sri

Lanka. The other cricket-playing countries such as England, Australia and New

Zealand only joined the boycott of South Africa at a later stage. Clive Lloyd,

also a former captain of the great West Indies team, who was not fully aware of

the socio-political-economic situation in South Africa, agreed to come to the

country to speak to all cricket administrators. But Mackerdhuj and his fellow

non-racial officials were totally opposed to Lloyd visiting South

Africa at a time when the white minority was still in control of the country.

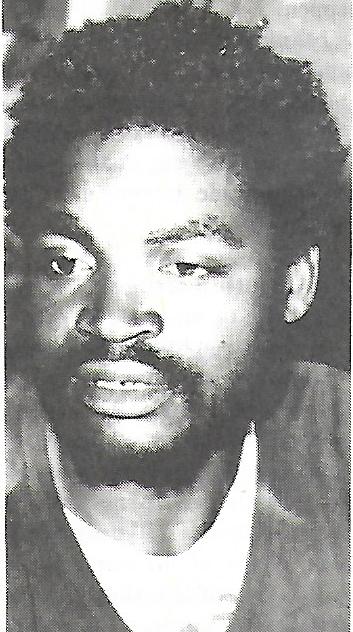

(Krish Mackerdhuj attending a

workshop at the Sastri College Hall in Durban in the 1980s when the struggles

against apartheid sport were at its height.) They had adopted the policy

of “no normal sport in an abnormal country”, a vision of Mr Hassan Howa, who

was president of the South African Cricket Board of Control (SACBC) in the late

1970s. The opposition by Mackerdhuj and his officials was fully supported by

the South African Council of Sport(SACOS), the United Democratic Front(UDF),

the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee(SANROC), which was based in

London; and the ANC in exile. I spoke to Mackerdhuj about their attitude to

Clive Lloyd’s proposed visit. He outlined that they respected the West Indian

great as a cricketer but they as South Africans knew when international

isolation of South African sport should be lifted. This is what Mackerdhuj had

told me in an interview at that time: “We have the utmost respect for Clive

Lloyd as West Indies captain and his efficiency and ability in cricket. The

system here would use him without any strings attached. They will go out of

their way to use him and that’s why people like Ali Bacher jumped to issue an

invitation to him. “By Lloyd coming here he would embarrass us. He must have

nothing to do with them. Change must come from within the country. People who

sit to talk must talk on an equal basis. There can’t be a master-slave

relationship. There can’t be a privileged person sitting with an

under-privileged person.” Mr Mackerdhuj, who in the early 1990s became the

first president of the new United Cricket Board of South Africa, was just one

of the hundreds of non-racial sports administrators who used sport to further

the struggles for a non-racial, just and democratic new South Africa. The

others included such luminaries as M N Pather, who was the secretary general of

the non-racial tennis union and SACOS; Don Kali, who was involved in the tennis

union; Mr Morgan Naidoo, who was leader of the non-racial swimming union; Mr

Norman Middleton, who was leader of the non-racial South African Soccer

Federation; Paul David, who was involved in the Natal Cricket Board and the

Natal Council of Sport (NACOS)and Mr Hassan Howa.

(Krish Mackerdhuj with Nelson

Mandela at a cricket match in the early days of the new South Africa.)

There were others such as Mr

Cassim Bassa, who was involved in table tennis, Mr Ramhori Lutchman, Dharam

Ramlall, S K Chetty and Mr R K Naidoo of the South African Soccer Federation

Professional League; and Mr Pat Naidoo and Harold Samuels of the Natal Cricket

Board. Mr Mackerdhuj in that interview in the early 1980s expressed the views

of his fellow anti-apartheid sports administrators when he had said that

“normal sport” could only be played and enjoyed once the country’s people were

also politically free. This is what he had told me: “You can’t have

discrimination in some fields and no discrimination in others. This is our

fight in sport. You can’t say there’s going to be no discrimination in sport

and yet we have discrimination in other aspects of our lives. We have made it

clear what we stand for, I don’t think the other side have made it clear what

they stand for. “And these people you know recently came out with a declaration

of intent and Ali Bacher was one of them. The Declaration was that they were preparing

for non-racialism in sport. “We say the declaration of intent by any sane

thinking person with interest in non-racial democracy in South Africa should be

against detentions without trial, against the unjust laws in the country,

against discriminatory education, against influx control, against the

activities of the police and defence forces in the townships. That’s the kind

of declaration that must come out of people who are interested in a future

non-racial and democratic South Africa.”

POLITICALLY CONSCIOUS

Mackerdhuj, who was born in

Durban in August 1939, had become politically-conscious after he matriculated

at Sastri College and studied at Fort Hare University in the Eastern Cape for

his BSC degree from 1958 to 1963. While at Fort Hare he joined the ANC but this

open involvement was shattered when the ANC and PAC were banned in 1960. He

told me that when he returned home in 1963 and joined Shell and BP as a

technologist, he had decided to use sport to further the cause of the ANC in

the struggles for a non-racial and democratic society. Although he was active

in soccer and table tennis, he had decided to concentrate on cricket, both as a

player and administrator. He joined the Crimson Cricket Club and thereafter

promoted the cause of non-racial sport through the Durban and District Cricket

Union, the Natal Cricket Board, the South African Cricket Board of Control and

later the United Cricket Board(UCB). In the ongoing struggles for a non-racial

and democratic society, he served the NCB as president for eight years from

1976-1984; president of SACBOC from 1984 to 1990; the South African Council of

Sport(SACOS) since its inception in 1970s and the Natal Council of Sport

(NACOS) as a founding member and president. In the struggles to isolate apartheid

South Africa, Mackerdhuj, after being denied a passport on several occasions,

travelled to London in 1987 to attend a meeting of the International Cricket

Council(ICC). Here he campaigned successfully with the help of Sam Ramsamy of

SANROC for South Africa to be banned from international cricket until apartheid

was abolished and the disenfranchised people people in South Africa attained

their political, social and economic freedom.

MACKERDHUJ AT LORDS IN LONDON

Mackerdhuj travelled to Lords

in London again in 1989 to present a petition to the ICC against the rebel tour

to South Africa by England’s Mike Gatting and his team. After the establishment

of a united cricket body following the release of Nelson Mandela and the

unbanning of the ANC in February 1990, Mackerdhuj served as deputy president of

the UCB for one year from 1992 to 1993 and as president from 1993 to 1997.

Mackerdhuj stepped down from the UCB in 1997 after he was appointed by

President Nelson Mandela to serve as Ambassador to Japan. He served South

Africa in this position for five years. During one of his visits back home at

this period, I again interviewed Mackerdhuj while I was working as a senior

political journalist at the SABC.

"MY NEW ROLE AFTER

FREEDOM"

He had told me that throughout

his life he had served the country and the ANC by campaigning for a non-racial

democracy through the medium of sport. “I am now happy to serve my country in a

new role after we have attained our freedom. We have a long road to travel

because we have to continue to work in all spheres to promote a better life for

all people. “We will have to be prepared to overcome many hurdles because the

road ahead will not be easy.” In the new South Africa, Mackerdhuj was presented

with a number of awards for his contributions to the struggles. These included

the State President’s Award for Sports Administration by President Nelson

Mandela in 1994; the Sports Administrator of the Year award in 1993 and 1994 by

the Natal Sportswriters Guild; and life member of London’s Marleybone Cricket

Club(MCC) in 1996. Mackerdhuj passed on, on the 26th of May 2004 at the age of

65. The role played by Mackerdhuj and others such as M N Pather, Morgan Naidoo,

Hassan Howa and George Singh should not be forgotten. But, unfortunately, 23

years into our new non-racist society, the contributions by activists of the

calibre of Mackerdhuj seems to have been trampled on by the return of racism in

many disguised forms. What a shame? What a sad commentary of the state of

affairs? Ends – subrygovender@gmail.com

.jpg)