(Mewa Ramgobin, George Sewpersadh and M J Naidoo travelled to Brandfort in the Free State to meet Winnie Mandela in 1983 after their banning orders were lifted. Also accompanying them were Paul David and Subry Govender)

September 16 2020

BY SUBRY GOVENDER

In October 1984, I had the privilege of interviewing

one of our social and political heroines, Ms Ela Gandhi, at a time when the

apartheid regime was conducting a reign of terror against resistance leaders. The interview was about her experiences two

months earlier when her late husband, Mewa Ramgobin, and other freedom fighters

– the late Archie Gumede, late M J Naidoo, late Billy Nair and Sam Kikine –

were detained by the then notorious security police. After they were released

15 days later following an application to the Pietermaritzburg Supreme Court,

Mewa Ramgobin and five others – M J Naidoo, George Sewpersadh, Archie Gumede,

Devadas Paul David and Billy Nair – sought refuge at the British Consulate

situated at that time in a building at the corner of the former Field (Joe

Slovo) and Smith (Anton Lembede) streets. After staying at the Consulate for

one month – Ramgobin, M J Naidoo and George Sewpersadh – walked out to

challenge the Pretoria regime’s oppressive stances. They were immediately

arrested and charged with 13 others with treason on October 6 1984. The trial

lasted until December 15 1985 when all of them were acquitted. The other

treason trialists were Paul David, Archie Gumede, Essop Jassat, Aubrey Mokoena,

Curtis Nkondo, Albertina Sisulua, Frank Chicane, Ebrahim Salojee, Ismail

Mohammed, Thozamile Gqweta, Sisa Njikelana, Sam Kikine and Isaac Ngcobo. Ela Gandhi Ramgobin in our interview in October 1984

told me about her trials and tribulations during the detentions and during the refuge

that Ramgobin and his comrades sought at the British Consulate.This is what we at the Press Trust of South Africa

Third World News Agency in October 1984 recorded of Ela’s experiences in her

own words:

Mrs Ela Gandhi (Ramgobin)

TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS

“Since August 21 (1984) – the day on which the Pretoria Government cracked down on opponents of its new tri-cameral constitution – the lives of many people have been rapidly and drastically affected by the events that followed.“As the wife of one of the detainees I would like to outline my own experiences. However, I would like to stress that in the South African context these experiences are not unique or isolated. Thousands of people are being daily subjected to unjust, arbitrary and surprise detentions.“Our leaders were detained on the eve of the Coloured Representative Council elections on August 21 after the United Democratic Front (UDF), the Natal Indian Congress (NIC) and the United Committee of Concern in Natal fought a long and arduous campaign against the so-called new constitution.“The detentions were preceded by a vicious campaign against the UDF and its leaders by the state-controlled radio and television services and by some state-influenced newspapers.“Right-wing student elements at white universities and the Indian and Coloured candidates also helped to whip up sentiments against our leaders and organisations. Cries of ‘communist ties’, ‘violent actions’ and other unfounded allegations were just part of the diatribe directed against our people.“My family became aware that a massive nation-wide swoop against our leaders was under way when we were rudely awakened by loud knocking on our door at our home in Everest Heights, Verulam, at 2am on August 21.“My son, Kush, who opened the door, was surprised and shocked when two security branch policemen pushed past him and entered the house.

“Within minutes my husband, Mewa, our four other children and I came to the lounge to see what the commotion was all about.“They told us that they had been instructed to take my husband into detention in terms of Section 28 of the Internal Security Act and they wished to search the house. They possessed neither a warrant of arrest nor a search warrant.“After a thorough search of the house for about an hour they found two books that belonged to me. One was a handbook on forced removals in South Africa and the other a book on the struggles by women in the country. I told them the books belonged to me and that they had no right to take them.“After a while they returned the books to me but left the house with my husband. I can say with pride that my children saw their daddy being driven away by the security police with courage and strength.“Trips to the police station, jail and our lawyers, which has now become a regular feature in our lives, began in earnest on the morning of August 21.“Our lawyers were able to see our husbands in detention at 11am. After being told that we could take food to our husbands we dashed to the nearest take-away to buy some food and cool drinks.“While our lawyers were allowed access to our husbands, we, the relatives, had to stand in the corridors of the C R Swart Square police headquarters (now Durban Central Police station) for quite a few hours without any seating being provided.“Eventually at 7pm, after supplying our husbands with ‘hot supper’ through an officer on duty, we left for home without seeing our men-folk. Half-an-hour later I had to attend an urgent meeting of the Natal Indian Congress and the United Democratic Front to discuss a rally planned for August 22.“I only went to my house in Verulam, which is about 25 kilometres from Durban, at 2am. The next morning at 8am I set out once again for C R Swart Square after attending to my home chores and taking care of the needs of my two sons and three daughters.

(Natal Indian Congress freedom fighters in the 1970s and 1980s)

“On arrival at the police headquarters my lawyer and

I were told that our menfolk – Mewa, Billy Nair, Archie Gumede, M J Naidoo

and Sam Kikine – were being transferred to the town of Pietermaritzburg to be

held in preventative custody.“We were allowed to exchange a few words with our

husbands through the cell doors.“That morning an executive member of the NIC,

Professor Jerry Coovadia, and I flew to Johannesburg to meet with the American

Ambassador, Mr Herman Nickel, and a British Embassy official, Mr Graham Archer.“We discussed the detentions and the propaganda

against our organisations. We called on the American and British governments to

actively support the democratic organisations in South Africa.

“We referred to the abstentions by the American and

British governments on the resolutions against South Africa at the United

Nations in New York and wanted to know what their attitudes were towards the

detentions.“We returned to Durban that same evening and rushed

to attend the mass rally at the Students’ Union Hall, University of Natal,

where more than 10 000 people packed every corner to listen to their true

and authentic leaders.“The massive turn-out of the people of all colours

was a clear indication of the support we enjoyed among all democratic-minded

people in South Africa.“The next morning heralded a period of contacts with

all the family members of the detainees, endless rounds of discussions with lawyers

and decisions on what steps to be taken in our campaigns to get our men

released.“We made three trips to Pietermaritzburg in two weeks

to obtain visits and give our leaders some clean clothes. The authorities,

however, refused to allow visits. We were only allowed to deposit some money

for the needs of our leaders and to give them clean clothes.“During this period of anguish and turmoil we, the

families of the detainees, grew closer, supported each other, shared our

anguishes and anxieties, and above all began to understand the unjust system

that robbed us of our menfolk.“This realisation brought us closer together to the

ideals and aspirations of the leaders in detention and gave us added strength

to fight for the cause – a cause for freedom, justice and democracy.“Fifteen days after our leaders were first picked up,

the Supreme Court in Pietermaritzburg upheld our application that the Minister

of Law and Order, Mr Louis Le Grange, had not given sufficient reasons and

information for detaining our menfolk.“Our leaders were allowed to go free but the prison

authorities only released them at 8:30pm that evening. After brief discussions

our leaders informed us that they would not return home with us because they

feared they would be re-detained. They wanted to take a ‘holiday’ for a few

days.“Although their decision was a painful one for us, we

accepted it because we also realised that re-detentions were a real

possibility.

(Mewa Ramgobin (Centre second row) with Paul David (left), M J Naidoo (right), George Sewpersadh (top left), Archie Gumede (centre) and Billy Nair who all occupied the British Consulate in late 1984 to highlight the oppression of the apartheid regime)

“Our fears were not unfounded. Within 24 hours Minister Le Grange issued new orders for their re-detentions. On September 9 at 1:30am we had another visit from the security police.“Like their first visit their entrance into our home was rude and typical of oppressors. When they did not find Mewa at home they became aggressive and talked of the possibilities of ‘our husbands being found dead with their throats slit and gullets hanging out’.“All the homes of the released leaders were similarly invaded that morning at the ridiculous hour of 1:30am. It is against this background of threats of ‘slit throats’, we learned with relief of six of our leaders making an ‘appearance’ at the British Consulate in Durban on September 13.

(Sam Kikine)

“We rushed to the Consulate offices to re-assure

ourselves that our menfolk were safe and in good health. But the British

consular staff refused to allow us to see our leaders.

“After lengthy and persistent negotiations, we were

allowed a brief re-union with our husbands – one family at a time for a few

minutes.“Having had the satisfaction of seeing them in good

spirits and good health, we felt a little ease at mind. But the following day

brought us face to face with the British ‘don’t care’ attitude when they

refused to allow us regular visits to our menfolk.“We immediately decided to resist by staging a sit-in

hunger strike at the Consul offices. Our protest brought in immediate results

for within half-an-hour we were told that visits would be allowed.“After the first week of the refuge at the consulate,

our anxieties for the safety of our

leaders grew when right-wing reactionaries threatened to blow up the building

where our husbands took refuge.“We began a 24-hour vigil at the building to monitor

all movements. This was called off after we noticed that uniformed policemen

had been posted to protect the building.“Our life of normal work and family routine was

disrupted. We now began to attend to the professional businesses run by our

husbands, arranging all their requirements at the Consulate – blankets and

pillows, cups and saucers, kettle and tea pots, chemical toilets, bath tubs and

daily meals and change of clothing.“We also had to attend and address meetings and

institute a new law suit against the Minister.

(Archie Gumede)

“After our case was dismissed, three of our leaders –

Mewa, M J Naidoo and George Sewpersadh – decided to challenge the authorities

by walking out from the consul offices. But no sooner had they appeared on the

street below, they were arrested by security policemen and taken to

Pietermaritzburg for preventative detention.

“Our anxiety and uncertainity began all over again

until we were allowed visits three times a week for a period of 40 minutes for

each visit.

“The visits were non-contact visits and were

separated by a glass window. We were allowed to converse through a

‘funnel-like” object.

“Although the journeys to Pietermaritzburg were long

and tiring, we were, however, pleased to make the trips just to see and talk to

our men folk.

“We have repeatedly asked the Minister for reasons to

justify the continued detention of our leaders but he has failed to respond.

“In our view there is no justification for the

detention of our leaders and we challenge the Minister to produce any evidence

to show that our men have propagated or participated in violence.

“We are proud of the struggle being waged by our menfolk and stand by them in spite of the daily suffering we endure.” Ends – Press Trust of South Africa Third World News Agency Oct 22 1984

HARASSMENT CONTINUES

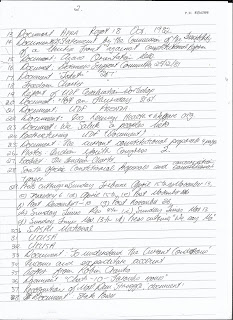

Then in the early hours of 5am on Feb 19 1985, security policemen raided the home of the Ramgobins in Everest Heights in Verulam, on the North Coast of South Africa.At this time Mewa Ramgobin and his fellow comrades had gone into hiding. The security policemen raided the home in search of Ramgobin and when they did not find him, they conducted a major search and confiscated scores of documents that belonged to Ela Gandhi and her late son, Kush.Some of the documents related to the Phoenix Settlement Trust, the United Democratic Front (UDF), the Azanian Peoples’ Organisation (AZAPO), Natal Indian Congress, Indian Youth Congress, Press Trust of SA News Agency, United Front Against Constitutional Proposals, and the African National Congress (ANC).

Mrs Ramgobin herself faced the full oppressive

actions of the apartheid regime when on August 31 1973 she was served with a

five-year banning order, which seriously affected her family and working life.

She had applied for her banning orders to be relaxed so

that she could take up a social worker’s position at the Durban Child Welfare

Society. But the then apartheid Minister of Justice at that time, P C Pelser, showed

her no mercy and did not even have the decency to respond to her pleas.

Her banning by the apartheid regime was aimed

primarily at suppressing her activist role in the struggles against the regime.

No comments:

Post a Comment