(Zwelike Sisulu and Juby Mayet leading a protest march in Johannesburg against the banning of the UBJ in 1977)

INTRO: The alleged

assassination threat by ANC MP Boy Mambolo against the Editor of the Star

newspaper, Sifiso Mahlangu, (Mercury Nov 8 2022), highlights the plight of

journalists who are fully committed to the freedom of the Press and freedom of

the society in our new post-apartheid and democratic society. Mahlangu’s situation merely reminds us that some

of the political leaders and political parties today are no different to those

of the past who used all kinds of violence, intimidation and harassment to

silence journalists who stood their ground against apartheid and minority rule.

Mahlangu is following in the footsteps of his predecessors during the apartheid

era who sacrificed almost everything for the freedom of the media. In order to

honour Mahlangu for his efforts for the freedom of the media, I would like to

remind South Africans in the following article of the journalists who fought

for the freedom of Press especially during the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s.

THE ASSASSINATION

THREAT AGAINST STAR EDITOR BY A RULING PARTY POLITICIAN REMINDS US OF THE

STRUGGLES OF JOURNALISTS DURING THE APARTHEID ERA

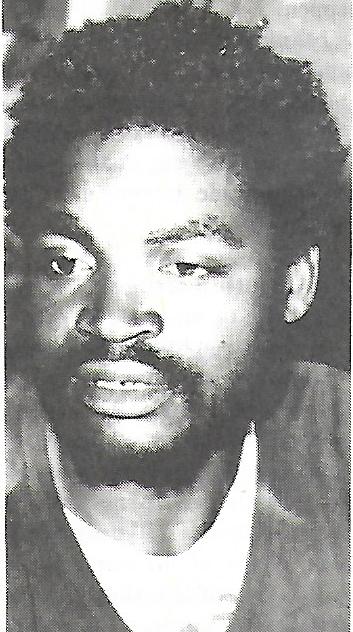

(Joe Thloloe)

By Subry Govender

When

we take a moment or two at this time to observe the situation of the Editor of

the Star, Sifiso Mahlangu, it’s crucial to recall the enormous sacrifices and

contributions of journalists during the apartheid era in the struggles for a

free, non-racial and democratic South Africa.

I am not going to go back in history but deal

primarily with the period when the then National Party introduced all kinds of

laws to suppress, oppress, harass and intimidate journalists – especially

journalists of colour.

(Philip Mthimkulu)

(Juby

Mayet)

Being colonial and racially

driven – the media during this period was mainly concerned with maintaining and

retaining white domination of the social, economic and political fabric of

South Africa.

Nearly all newspapers were

white owned, controlled, managed and edited – with the exception of one or two

minor and insignificant publications – and the National Party monopolised the

airwaves in the name of the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC).

(Leslie Xinwa)

(Isaac Moroe)

(Nat Serache)

(Rashid Seria)

(Mathatha Tseudu)

The apartheid regime,

especially under the leadership of John Vorster, Hendrik Verwoerd and P W

Botha, had in their arsenal more than 100 statutes that limited the freedom of

the Press. The repressive atmosphere really began after the Sharpeville

uprisings on March 21 1960 when police shot dead 69 peaceful marchers who were

protesting against the carrying of the hateful Dom-Pass.

The National Party

Government introduced a state of emergency and banned the ANC and the PAC and

crushed all opposition to white minority rule. Publications such as the New

Age, Fighting Talk, Advance and Guardian were forced to close shop and the

journalists working in these and other progressive newspapers either had to

flee the country or go underground.

(Matyeu Nonyane, Rashid Seria, Leslie Xinwa

and Isaac Moroe)

During this period of

repression, some of the only black-oriented newspapers that were allowed to

operate were the Drum magazine and the Golden City Post. Although they reported

on some political developments, they were, however, no danger to the existence

of the white state.

Being white-owned and managed, these newspapers concentrated on the sensational

– sex, crime and gangs and sport – in order to survive. There were some

journalists during this period in the 1980s who dared to question the white

status quo – but they too were quickly intimidated and forced to flee the

country or tone down.

(Mona Badela and Enoch

Duma)

In the early 1970s – when

the black consciousness movement took root after the establishment of the South

African Students Organisation (SAS0) – a number of journalists came to the fore – prepared to

take on the white oppressors irrespective of the consequences. These

journalists were primarily working at that time for newspapers such as the

World and Weekend World, and socially-conscious journalists working for

mainstream newspapers such as the former Rand Daily Mail, the East London Daily

Dispatch, the Cape Times and Argus, the Johannesburg Star and the Durban Daily

News.

They tried to introduce a

new and dynamic approach to journalism by tackling the social, economic,

sporting and political oppression of the majority. The struggle for freedom of

the Press and the liberty of the people had just started in earnest once again.

But no sooner had journalists – with a black consciousness

background – begun to tackle real and fundamental issues affecting the

majority, the apartheid system struck back with a vengeance in 1974 when they

banned a Frelimo rally scheduled to be held at Durban’s Currie’s Fountain and

prohibited any newspaper coverage of the event.

As a matter of interest,

black consciousness leaders like the late Strini Moodley, Saths Cooper, Aubrey

Mokoape and others were charged under the infamous Terrorism Act and as a

result of the rally were charged and sentenced to Robben Island.

(Journalists standing up

for Media Freedom in the 1970s and 1980s)

Further onslaughts against

the media began after the 1976 Soweto uprisings. Two months after the

uprisings, nine journalists, who played a leading role in reporting events in

Soweto, were detained under the regime’s Internal Security Act, and two others

were incarcerated under Section 6 of the Terrorism Act.

Among the very first to be

arrested was Joe Thloloe, who was at that time working for the World Newspaper;

Peter Magubane, South Africa’s world-famous photo-journalist who worked at that

time for the Rand Daily Mail and Miss Thenjiwe Mntintso, who worked at the

Daily Dispatch in East London at that time.

The majority of them were

held for about four months without being tried in a court of law. They were

released at the end of December 1976 but some were re-arrested in 1977. Joe

Thloloe was held incommunicado for 547 days under Section 6 of the Terrorism

Act.

(Rashid Seria, Mike Norton

and Juby Mayet at a UBJ meeting in Durban in 1977)

The others were Willie

Bokala, a reporter for the banned World newspaper who was held in detention for

more than a year; Jan Tugwana, a reporter for the then Rand Daily Mail who was

also held in detention for more than a year under Section 6 of the Terrorism

Act; Ms Juby Mayet, a doyen of journalists who was held incommunicado under the

Internal Security Act at the Fort Prison in Johannesburg; Isaac Moroe, the

first president of the Writers Association of SA (WASA) in Bloemfontein; Bularo

Diphoto, a freelance journalist in the town of Kroonstad who was also detained

under Section 6 of the Terrorism Act; and Mateu Nonyane.

Another journalist, Mr

Moffat Zungu, who was a reporter for the World Newspaper, was an accused in the

Pan African Congress (PAC) trial that took place in Bethal, near Johannesburg.

He was first detained under Section 6 of the Terrorism Act.

The darkest day in the

history of Press Freedom took place on October 19 1977 when the notorious

apartheid Minister of Police, Jimmy Kruger, banned the only two newspapers

respected among people – the World and Weekend World.

(Charles Nqakula, Subry Govender and Philip Mthimkulu)

Mr Kruger, who became

infamous for describing Steve Biko’s death two months earlier as – “It leaves

me cold” – at the same time banned the Union of Black Journalists (UBJ) and 17

other organisations; the publication of the UBJ – AZIZTHULA; religious and

student publications; locked up the editor and news editor of the World and

Weekend World – the late Percy Qoboza and the late Aggrey Klaaste respectively;

and banned for five years the Editor of the Daily Dispatch, the late Donald

Woods.

The regime also raided the

offices of the Press Trust of South Africa (PTSA) alternative news agency in

Durban and confiscated all its stationery and equipment and seized its funds.

Six other journalists were

also detained at this time – including Thenjiwe Mntintso, who became an ANC

functionary after 1994 and appointed as an ambassador; and Enoch Duma – who

worked for the Star newspaper at that time. He fled into exile after being released

after more than two years in detention.

Almost every member of the

UBJ was visited by the security police all over the country; their homes and

offices raided and searched and interrogated. All the raids were carried out at

the unearthly hours of 4am and 5am in the morning. I remember my mother

knocking on my door and saying in our Tamil mother tongue: “Some white people

are here asking for you.”

When representations were

made to Mr Kruger for the release of the detained journalists, he had the temerity

to announce that the detentions were not meant to intimidate the Press and that

his Government had good reasons to detain the journalists.

It was during this

traumatic period that another publication of the UBJ, UBJ Bulletin, and all

subsequent editions were banned. The UBJ Bulletin contained some revealing

articles about the activities of the South African Police during the Soweto

uprisings. Four UBJ officials – Juby Mayet, Joe Thloloe, Mike Nkadimeng and Mike Norton – were charged for producing an

undesirable publication.

Inspite of world-wide

condemnation of the banning, detention and harassment of journalists, the state

security police continued with their jack-boot tactics.

In Durban two Daily News

journalists – Wiseman Khuzwayo and Quraish Patel – were detained without trial

for more than three months.

On November 30 1977, the

day white South Africa went to the polls to give John Vorster another mandate

to continue to oppress the majority, 29 journalists, including Zwelakhe Sisulu and Ms

Juby Mayet, staged a march in the centre of Johannesburg against the banning of

the UBJ and the detention of journalists. They were detained for the night at

the notorious John Vorster Police station and charged under the Riotous

Assemblies Act and fined R50 each.

Some of our colleagues who

found it impossible to continue to work in South Africa skipped the country

under trying circumstances. They included Duma Ndhlovu, Nat Serache, Boy

Matthews Nonyang and Wiseman Khuzwayo.

Those who remained – including

Juby Mayet, Zwelakhe Sisulu, Philip Mthimkulu, Joe Thloloe, Charles Nqakula,

Rashid Seria, this correspondent and many others – vowed to continue the

struggle. We committed ourselves in the belief that there could be no Press

freedom in South Africa as long as the society in which we lived was not free.

But the regime was also determined to make life difficult for us.

In July 1977 when we

scheduled to hold a gathering of former UBJ members in Port Elizabeth to chart

our future course of action – the regime banned our gathering and prohibited us

from travelling to the PE. But being determined to take on the regime head-on

we quickly re-scheduled our meeting to be held in the town of Verulam, about

25km north of Durban.

Unknown to us the dreaded

Security Police tapped our telephone conversations and had the Starlite Hotel

in Verulam bugged. The Security Police were listening to the entire proceedings

of our meeting and immediately decided that we were a bunch of “media

terrorists” who should be taken out of society.

At our meeting we decided

to establish our own daily and weekly newspapers and a news agency because we

were of the firm belief that the establishment media was not catering for the majority. The establishment media of that era,

as you have already been informed, was aimed at protecting and promoting the

privileges of the minority.

But, sadly we did not have

the resources to embark on such ambitious projects. Nevertheless, many of us

who became frustrated with the establishment media began to make arrangements

for the establishment of regional newspapers that would provide an alternative

voice to the mainstream media and the National Party-controlled SABC.

But resistance led to more

repression. In June 1980 when school children all over the country boycotted

classes against the unequal and inferior education system for children of the

majority, the security police once again targeted journalists. They detained

many of us for lengthy periods, claiming that the journalists had been encouraging

the children to boycott classes.

Zwelakhe Sisulu was during

that period of repression detained for nearly two years.

In Durban, Cape Town, Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth, East London and other

centres – black journalists continued to work with the community in an attempt

to establish alternative newspapers.

In Durban, the Press Trust

of South Africa Third World News Agency was established as one of the first

moves to provide the outside world with accurate information about the

situation in South Africa. The news agency was established to operate alongside

the running of the alternative newspaper, Ukusa.

But just when the newspaper

was set to start publishing with the blessing of the community, the state

struck again and banned its Managing Editor – this correspondent; and also

Zwelakhe Sisulu, Joe Thloloe, Philip Mthimkulu, Mathatha Tsedu and Charles

Nqakula in December 1980.

This was a massive blow for

the alternative media because all the journalists were fully involved in the

various projects.

Some of the publications

that they were involved in were UKUSA in Durban, Grassroots in Cape Town, Speak

in Johannesburg and Umthonyama in Port Elizabeth. The South African Council of

Churches also sponsored the publication of a newspaper called The Voice. Philip

Mthimkulu and Juby Mayet worked for this newspaper before they were banned.

The journalists in question

were put out of circulation for three years until the end of 1983 when their

banning orders expired. But during their period of forced exile, the journalists

did not remain idle – for instance the Press Trust of South Africa News Agency

continued to operate under some trying conditions, intimidation and harassment.

During this period Charles

Nqakula skipped the country to join the ANC. Upon his return he served the new

government in various positions, including Minister of Defence.

When our banning orders

expired, most of us continued where we had left off. In Johannesburg, Zwelakhe

Sisulu initiated the establishment of the New Nation newspaper with the

assistance of the South African Catholic Bishops Conference; in Cape Town,

Rashid Seria initiated the establishment of the South Newspaper; and in other

parts of the country many other progressive forces and journalists began to

establish alternative publications.

The apartheid regime began

another round of repression and during the respective states of emergency,

media repression reached a peak. It was a time when the discredited tri-cameral

system was in place and the United Democratic Front had captured the

imagination of oppressed South Africans.

Most of us – who were in

the forefront of the alternative media – were under constant surveillance. For

instance during the emergency regulations in 1986 and 1987 – the dreaded

security police at that time raided all the alternative newspapers and

intimidated the journalists.

The New Nation and the Weekly Mail – two alternative newspapers in Johannesburg

– were banned several times from 1986 to 1990.

When peace negotiations

began, there was some respite for journalists and the media.

The stand-point taken by

Sifiso Mahlangu, Editor of State, is a reminder once again to journalists of

today that they must recapture the struggles of the journalists of the era

prior to 1994 and commit themselves to promoting media freedom in our new, non-racial

and democratic order.

The new era journalists

must be on guard all the time. They must remember that a country without a free

media is not free at all and this must be communicated to the current people in

political power.

Our first democratic

president, Nelson Mandela, repeatedly told us how much he appreciated the work

that struggle journalists had done for their freedom and how it was important

that media practitioners continued to keep a check on the new politicians. He made

it clear that the new politicians are answerable to the citizenry and not the

other way round.

What Mandela was saying was

that journalists must keep a check on politicians who try to harass, intimidate

and use violence in order to curb the freedom of the Press in our new

non-racial, democratic and free South Africa. Ends – subrygovender@gmail.com Nov 9 2022

.jpg)